uncover

Wolf Facts & Myths

How does confusion between facts and myths about wolves lead to conflict?

Wolves stir up strong emotions in people. They are either loved or hated, respected or feared, considered a relative or an enemy. Feelings about them are complicated. Think about your own perceptions about wolves – they are influenced by the media you consume, people you listen to, and your education, culture, folklore, values, beliefs, and personal experiences. Despite being one of the most researched animals in the world, wolves are also one of the most misunderstood. Misperceptions about wolves are often based on myths or misinformation, and have inspired decades of scientific research in search of the facts. A massive body of evidence is now available to dispel myths and help people understand the truth about the wolf, its role in its ecosystem, and its relationship with people.

Watch this video to learn how to write about facts and myths so that people remember the facts, according to the research.

Read about the myths below that interest you, and the facts that debunk them. Watch the videos and respond to the Points to Ponder. Which of the myths on this page have you heard before? As you read them, consider your own past and current perceptions about wolves.

What do these scientists, Indigenous Knowledge Keepers, and websites say about wolf facts and myths?

- Visit these two webpages that describe myths and contrary facts about wolves. Which one or two surprised you? Share the myth with the facts that disprove it.

- Watch the two video interviews with Indigenous Knowledge Keepers and wolf scientists. What is said in each that dispels a myth about wolves?

- Think about and discuss how believing in one of these myths, instead of the facts, can affect how a person feels about peacefully coexisting with wolves with minimal conflict.

FACT: Any predator can be dangerous to people, but wolf attacks are rare.

MYTH: "Wolves attack people."

Evidence: Many people think wolf attacks are common, but it is more likely that you will be attacked by a bear or mountain lion¹. There have only been two documented cases in the last century where wild, unprovoked and healthy (non-rabid) wolves killed humans in North America². In both cases, the people were alone in areas where wolves were habituated to humans³. Wolf attacks on humans usually occur because the wolf in question is provoked, surprised, or rabid, or because it detects a prey flight response from the person. The vast majority of these attacks are not fatal.

In general, wolves are shy animals and fear humans enough to avoid them⁴ ⁵. If a person does encounter a wolf, the animal’s behavior would let the person know if it was feeling threatened or aggressive. Wolves display particular vocalizations and body language when they are preparing to attack potential prey. As long as people are aware of these behaviors and the appropriate response to them, they can avoid putting themselves in a dangerous situation where an attack could occur⁶ ⁷ ⁸.

FACT: Wolves are opportunists, choosing to hunt prey that are easiest to catch and kill using the least amount of energy.

MYTH: "Wolves kill animals for sport as well as for food."

A commonly held perception is that wolves will kill animals for sport as well as for food. The success rate for wolf chases that result in kills is only 14%, with 86% of the chases ending with no food¹! These predators can’t afford to waste energy chasing and killing for reasons other than getting food. Hunting is also dangerous for wolves because they are trying to take down prey much larger than they are. Working together as a pack may reduce the risks, but a swift kick from an elk or bison can cause injury and death to an individual. Packs will strategically target the young, old, or sick individuals to reduce their chances of injury or death. As a bonus, eliminating these weaker individuals from the herd also helps to keep prey populations healthy.

The perception that wolves kill for sport may have come about due to the phrase “surplus kill,” which refers to instances when wolves kill more prey than they can eat in one sitting. Given the challenging nature of the hunt, surplus kills are not a sport but rather a smart move² ³. Scientists and wolf experts have learned that wolves never waste food. They will always return to the kill to finish eating if humans or scavenger animals haven’t gotten there first⁴. Why might wolves kill more than they can eat? Reasons include preparing for long, cold winters when food sources are rare⁵, and taking advantage of opportunities for an easy kill⁶.

FACT: Wolves kill elk and deer for food, but will not reduce the populations enough to eliminate hunting opportunities.

MYTH: "Wolves will decimate populations of elk and deer, and eliminate the hunting season."

A common perception is that wolves significantly reduce elk and deer populations, meaning very few hunting permits will be issued. It is true that prey populations will be affected, given the natural predator-prey relationship. However, these populations will not drop enough to eliminate the opportunity for people to hunt these animals altogether.

In states with large wolf populations (Montana, Idaho, and Wyoming), elk numbers are close to or above target levels set by state wildlife agencies¹ ² ³. Research from Yellowstone provides data on elk populations before and after wolves were reintroduced. Before the 1995 reintroduction, elk numbers had already started decreasing.

When wolves were released, elk numbers dropped further, leading many people to believe wolves were the cause. However, other factors like summer precipitation, winter severity, and hunting by other predators were also affecting elk population size⁴. Despite the correlation of elk population decline and wolf reintroduction, it is unclear if the primary cause of Yellowstone’s declining elk populations was an increase in wolves.

To understand the effects of wolves on the hunting season, it is helpful to examine how hunting strategies of predators and humans differ. Wolves are opportunists, meaning they choose the easiest animals to hunt. To survive, wolves need to successfully kill prey by using the least amount of energy without getting hurt. They rarely attempt to kill a strong, healthy, and dangerous adult. Instead, they go after the herd’s young, old, and sick, the opposite of human hunters, who prefer taking the healthiest individuals in the herd⁵. Most female elk hunted by people are within the reproductive ages of 2-8 years old, while 80% of the females killed by wolves from 1995-2011 in Yellowstone were more than 10 years old⁴. Research suggests that wolves preying on the sick can reduce brucellosis and possibly even chronic wasting disease, which could improve the overall health of elk herds and have a positive impact on human hunting⁶ ⁷.

FACT: Wolves only prey on livestock when other prey is not available, or if the wolf in question is weak or old.

MYTH: "Wolves would decimate livestock herds and cause economic devastation to ranchers."

One of the most common misperceptions surrounding wolves is that they will decimate livestock herds and cause economic devastation for ranchers. However, experts have learned that wolves only turn to livestock as a food source if their other food sources are not available, or if the wolf in question is weak or old¹ ². In states where wolves are the most common (Montana, Idaho, and Wyoming), wolf attacks account for less than 1% of cattle deaths caused by predators³ ⁴ ⁵ ⁶. It is important to note that this statistic is looking at the total number of wolf attacks on livestock in the state, and does not distinguish between different impacts on large vs. small ranches. If a domestic animal is killed on a small ranch, the impact could be significantly higher than suggested by this statewide data. However, states with wolves have set up compensation programs to pay ranchers for their monetary loss caused by the depredation of one or more of their livestock⁷ ⁸. There are also a wide variety of non-lethal strategies that ranchers can use to to avoid or deter wolf attacks on livestock⁹.

FACT: As with most other animal species, wolves will migrate from their home range into other places if the habitat will support them.

MYTH: "Wolves will not leave their home range."

Wolves have no concept of borders, as is evident in past cases when they have naturally expanded their range after reintroduction in a particular place. When species migrate to areas in their historic range, this process is known as recolonization. For example, before the Yellowstone reintroduction in 1995, Canadian wolves had begun to naturally recolonize Montana. After the Yellowstone reintroduction, the wolves within the park expanded their home range into the surrounding states of Montana, Idaho, and Wyoming. Even today, wolves are slowly moving into eastern Oregon, Washington, and even northern California¹.

FACT: Approaching any wild animal, especially a predator, can be dangerous for both the person and the animal.

MYTH: "People can get close to wolves without concern about getting hurt."

Even though the perception of wolves as dangerous killers is exaggerated, it is not safe for people to approach them or try to interact with them¹. Most instances of wolves attacking humans occur either when wolves become habituated to (comfortable with) people, or when a person runs away from the animal. Fleeing can trigger a wolf’s predatory response to chase “prey”². As with any predator, wolves are not dangerous when they are given space to move away, do not feel threatened, and are not put in a situation where they could see people as potential prey. As long as people learn about wolves’ needs and natural behaviors and use common sense, they can avoid encounters that are dangerous to both themselves and the wolf.

FACT: Taking wolves out of an ecosystem can have negative impacts, and bringing them back can offer positive impacts.

MYTH: "Reintroducing wolves to an ecosystem will completely restore it to its previous state."

Scientists agree that wolf extirpation had negative impacts on the ecosystems in question, and that bringing wolves back can offer positive impacts for these places¹. However, the amount and type of impact is the subject of continued research.

When people eradicated wolves from most of their historical range, elk populations shot up and the health of those ecosystems declined. The land changed dramatically as increasing numbers of these ungulates overgrazed woody plants like willows and aspen. It seems logical that bringing wolves back would reverse the effects on elk and the land. In fact, it is more complicated.

The relationships among the many parts of an ecosystem are quite complex, making it difficult to say that one species is essential for maintaining that ecosystem’s balance² ³. Organisms and nonliving parts of ecosystems are part of an intricately connected web. Removing any species from that web, especially a major predator like the wolf, will be disruptive and change the way that system works.

Since wolves have been absent from much of their historic range for decades, it is difficult to predict the effects of putting them back based on what the ecosystem looked like when the animal was first removed. History and biology show that wolves could help restore health and balance to these ecosystems. However, historic wolf habitat has undergone much change since wolves were eliminated. Scientists can only predict how today’s ecosystem will be affected by the return of this predator, but evidence from previous reintroductions suggests the effects could be positive.

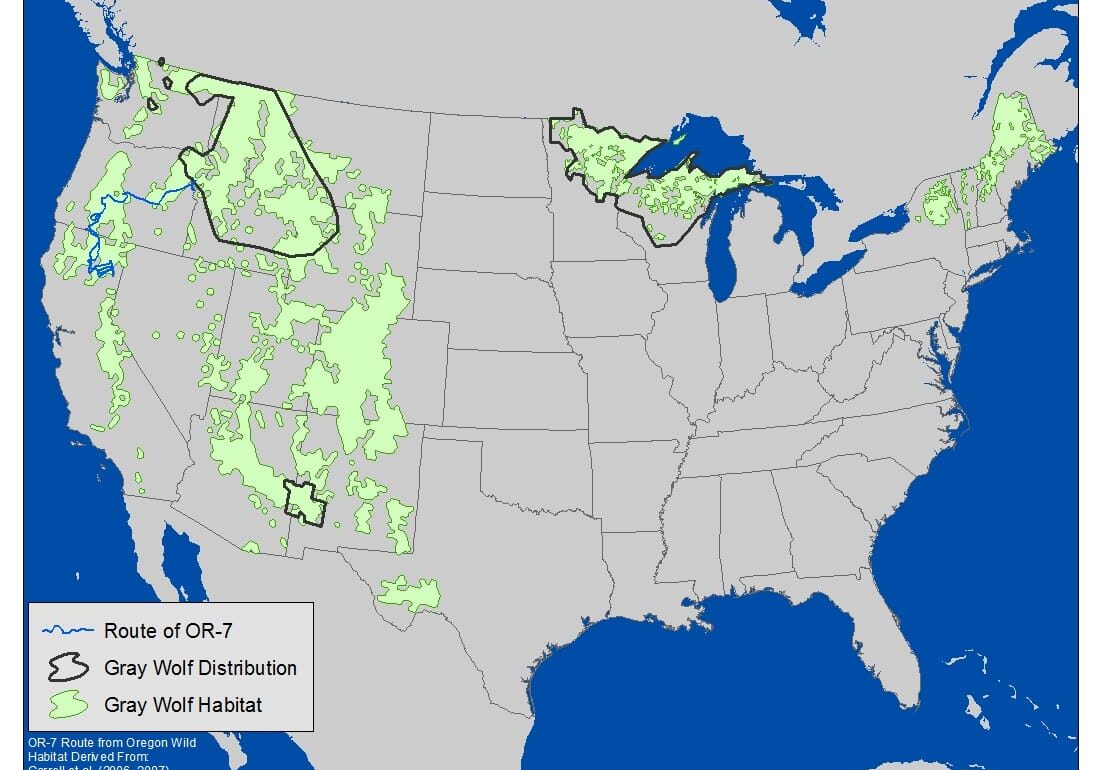

FACT: Wolves now live in only 10% of their historic range in the continental 48 states.

MYTH: “Gray wolves live across the US.”

Before colonial settlers traveled across the United States in the early 1800s, wolves were common across much of the continent and what is now the lower 48 states¹ ² ³ ⁴! That range has been drastically reduced because of habitat loss and actions of people to eliminate wolves in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s.

Watch the video of street interviews with Colorado citizens. Separate the myths they believe from the facts about wolves living in their state. (Note: Colorado's last wolf killed in 1945. In 2020, Colorado voted to reintroduce wolves over the next few years. This video was produced before reintroduction began.)

Then find where you live on the maps. Are you living in the historic range of wolves? Are there wolves living in your state, or near you today? Click on the maps to enlarge and interpret the data. Respond to the Points to Ponder by examining the maps.

FACT: Coyotes and large dogs are commonly mistaken for wolves. Wolves are very shy, and stay away from people.

MYTH: "It's common to see wolves when out in nature and even around town."

Test your observation skills! Is it a wolf, a coyote, or a dog?

These wolf-coyote-dog identification guides help people who live in near wolf habitat to tell the difference between these three groups of animals. Based on the misperceptions shown in the video, these guides would also be helpful to people living in the coyote's larger habitat.

Open one of these guides and practice accurately identifying the animals in the photos. Is it a wolf, a coyote, or a dog?

FACT: Sometimes killing wolves reduces the number of livestock they kill, while other times the number stays the same or actually increases.

MYTH: “Killing wolves is an effective way to reduce the number of livestock they kill.”

Why would the number of livestock killings increase? When a pack loses a wolf, it also loses that wolf’s hunting knowledge and experience. To be able to survive, the disrupted pack goes after animals like livestock that are easier to hunt successfully.

Why might the number of livestock deaths stay the same? When one rancher kills a wolf, the remaining wolves might simply move to the neighbor’s herd. The neighbor would see an increase in predation by wolves, wiping out the benefit seen by the rancher who killed the wolf. The total number of livestock killed in an area would not change.

When would killing a wolf help reduce the number of livestock killed? When looking at a small localized area, killing a targeted “problem” wolf could reduce local conflict. Research and debate continues around the effectiveness of killing wolves.

Article: These non-lethal methods encouraged by science can keep wolves from killing livestock, Smithsonian Magazine