explore

Migration & Hibernation

How and why do some pollinators migrate or hibernate?

Some pollinators are not able to live all year in one ecosystem because of changes in seasons or lack of available food. If these pollinators are to survive, they must either migrate by moving to another ecosystem, or hibernate by slowing down their body systems in a quiet dormant state. An animal’s ability to migrate or hibernate is affected by its physical and behavioral adaptations, its needs in different stages of its life cycle, its role in a food web, and what it needs from its ecosystem.

Migration usually happens as seasons change. When temperatures drop, pollinators will move to warmer climates where they can continue to find plenty of food. Some pollinators are known to travel as many as 1,000 miles between their summer to winter habitats just to survive. They might use your community as a summer home, a winter home, or as a migratory corridor - the route taken on the animals’ journey between summer and winter habitats. These corridors provide pollinators essential rest and food stops on their long journeys. Migration decisions and food needs are dependent upon local weather and climate. As climate patterns change, many pollinators are forced to adapt their migration patterns in order to survive.

Hibernation is when animals slow down their body systems, typically during the winter, to cope with threatening weather conditions and low food availability. To prepare for hibernation, pollinators must increase the amount of food they eat and store, and find a safe place to hide until weather and food conditions improve and they can become active again.

On this page we'll EXPLORE the migration and hibernation patterns of each pollinator group. Understanding these patterns can help you help your pollinator species. Find your species' pollinator group, read about its migration or hibernation pattern, and respond to the Questions to Consider.

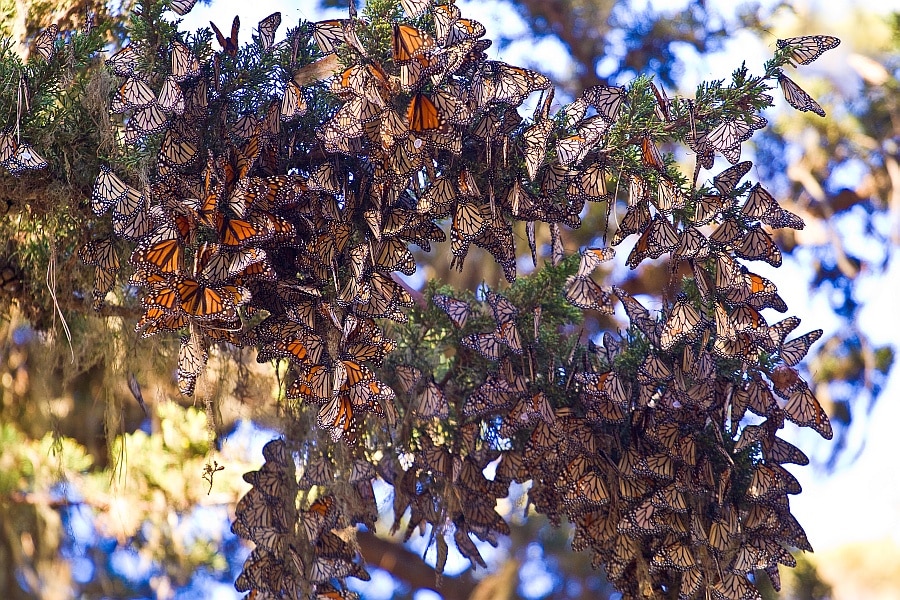

Butterflies, Skippers & Moths

There are several species of butterflies, skippers, and moths that migrate. The most well-known migration is that of the monarch butterfly, which migrates from summer habitats as far north as Canada to winter habitats in either Southern California or a small mountain range in Mexico. In the spring, the same monarch that flew hundreds or even thousands of miles south begins its journey back north to lay eggs on milkweed plants for the summer season. Once eggs have been laid, this generation of monarch dies. The next generation of young that hatch then continue the journey north to summer habitats across the USA and Canada. Other species that migrate include the painted lady, gulf fritillary, cloudless sulphur, American lady, question mark, mourning cloak, red admiral, and more. Migration and hibernation patterns vary from species to species of butterfly, skipper, and moth. Consider diving deeper into researching your species' unique migration and hibernation!

Questions to Consider:

- What is this pollinator group's pattern for migrating or hibernating when seasons change?

- At what stage in their life cycle does your species migrate and/or hibernate?

- How would understanding patterns of migration or hibernation help you help your pollinator species?

Hummingbirds

Many species of hummingbirds spend the winter in Central America or Mexico. They begin to migrate north to their breeding grounds in the southern U.S. and western states as early as February, and to areas further north later in the spring. Some hummingbirds that live in warmer areas like California do not migrate. When they migrate they fly low and fast, traveling as many as 23 miles per day. In order to have energy to make the journey, a hummingbird will consume copious amounts of food and gain 25-40% of its body weight as energy stores. Birds use the magnetic fields of the earth to help them navigate.

Questions to Consider:

- What is the hummingbird's pattern for migrating or hibernating when seasons change?

- At what stage in their life cycle do hummingbirds migrate and/or hibernate?

- How would understanding patterns of migration or hibernation help you help your pollinator species?

Bats

The species of pollinating bats we find in North America are important pollinators of desert plants in the southwest United States and northwest Mexico. Every night, each of these bats will fly as many as sixty miles to gather the nectar it needs. They must follow the flowering seasons of these cacti and desert flowers to survive and thrive. This means following their “nectar corridor” south into the warmer climates of Mexico’s deserts during the winter months. In the spring, they come back up to the American Southwest to give birth and mate. Each migration may take one of these bats on a 3,200 mile loop through deserts and mountain terrain.

Questions to Consider:

- What is the bat's pattern for migrating or hibernating when seasons change?

- At what stage in their life cycle do bats migrate and/or hibernate?

- How would understanding patterns of migration or hibernation help you help your pollinator species?

Bees

Bee species do not migrate during the winter, instead choosing to hibernate. An exception is non-native honey bees, which do not hibernate. They keep the hive warm by forming a “winter cluster,” which means they all huddle together and shiver to provide warmth.

Questions to Consider:

- What is the bee's pattern for migrating or hibernating when seasons change?

- At what stage in their life cycle do bees migrate and/or hibernate?

- How would understanding patterns of migration or hibernation help you help your pollinator species?

Curious to know more about the pollinator you want to help?

Go beyond this Quest page to explore more about the pollinator species you have chosen to help.

- Why does your pollinator species migrate or hibernate?

- How do your pollinator's adaptations help it migrate, hibernate, or to live actively in the same habitat all year? (recall its Adaptations)

How is your pollinator being affected by human activity?